A choice is not a choice if it is made in the context of fear.

Informed choice is a popular phrase with birth professionals and healthy birth activists. I’ve read impassioned blog posts from doulas and birth activists claiming that if we support women’s right to homebirth, we must also support her “choice” to have an elective cesarean. But, I believe we have constructed a collaborative mythos within the birth activist community that an informed choice is possible for most women. The statistics tell us a different story. I do not believe that women with full ability to exercise their choices would choose many of the things that are typically on the “menu” for birth in mainstream culture.

What’s on the menu?

Women give their blanket “informed consent” to all manner of hospital procedures without the corollary of informed refusal–is a choice a choice when you don’t have the option of saying no?

In many hospitals, women are STILL not allowed to eat during labor despite ample evidence that this practice is harmful–is a choice a real choice if made in the context of hospital “policies” that are not evidence-based?

Women are told that their babies are “too big” and then “choose” a cesarean. Is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of coercion and deception?

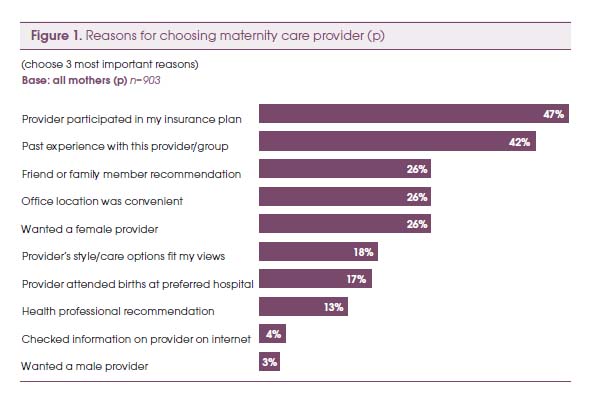

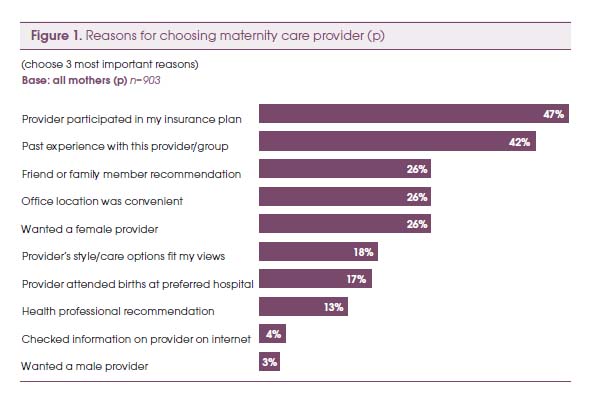

Women choose hospitals and obstetricians that are covered by their insurance companies. Is a choice a real choice when it is made by your HMO?

Women choose hospital birth because they cannot find a local midwife. Is a choice a real choice when it is made in the context of restrictive laws and hostile political climates?

Women often state they are seeking “balanced” birth classes that aren’t “biased” towards natural birth (or towards hospital birth), but is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of misrepresented information? Because, as Kim Wildner notes, balance means “to make two parts equal”–what if the two parts aren’t equal? What is the value of information that appears balanced, but is not factually accurate? Pointing out inequalities and giving evidence-based information does not make an educator “biased” or judgmental–it makes her honest! (though honesty can be “heard” as judgment when it does not reflect one’s own opinions or experiences).

On a somewhat related note, recently, the subject of “quiverfull” families came up amongst my friends and comments were made about feminists needing to support those women’s “choice” to have so many children. However, I worry about women who are making reproductive “choices” in the context of what can be a very repressive religious tradition. Women’s choices about their lives are not always made with free agency. And, that is where some feminist critiques of other women’s choices come from–a critique of the larger context (patriarchy) rather than the woman herself. Is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of oppression?

Where do women get information to make their choices?

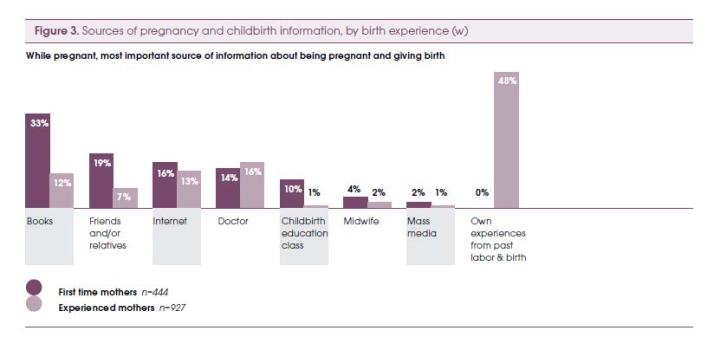

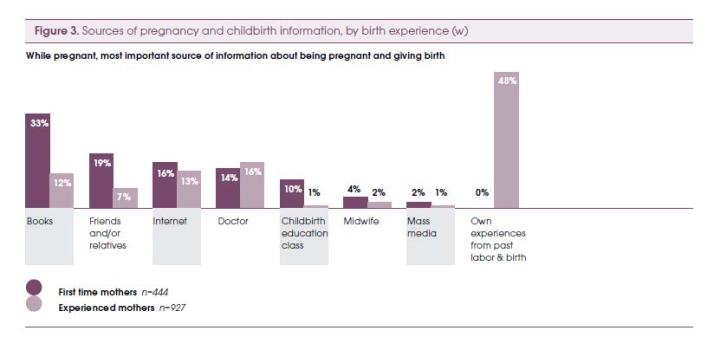

In his 2010 presentation, Birthing Ethics: What You Should Know About the Ethics of Childbirth, Raymond DeVries uses data from the Listening to Mother’s studies to help us understand where women are getting their information about birth—this is the context in which their “informed choices” are being made and this is the context we need to consider.

Our choices in birth and life are profoundly influenced by the systems in which we participate…

Some choices shaped by the system

Women learn from books and experiences of others (and self):

The number one book women learn from is What to Expect When You’re Expecting, which has been number four on NY Times Bestsellers list for over 500 weeks and counting.

According to De Vries, via the Listening to Mothers data, this is what women tell us about how they learn, what they learn, and upon what their choices are based:

Television explains birth

Pain is not your friend

But technology is

Mothers are listening to doctors (and nurses)

Medicalized birth allows mothers to feel capable and confident

Interfering with birth is mostly okay

Our health system works (mostly)

We like choice

We want to be “informed”

He also explains polarization: “We seek information to confirm our opinion. Contrary information does not convince, it polarizes.” How do we share information so that women can make truly informed choices without polarizing?

As advocates, I think we sometimes fall back on the phrase “informed choice” as an excuse not to be outraged, not to despair, and not to give up, because it promises that change is possible if only women change and most of us have access to change at that level.

Birthing room ethics

In another presentation, U.S. Maternity Care: Understanding the Exception That Proves the Rule, DeVries explores the ethical issues surrounding choices in birth, noting that “choice is central at all levels – but can choice do all the moral work?” We wish to respect parental choice, but information does not equal knowledge and we often err on the side of treating them as one and the same. In maternity care, often there is no choice. Tests become routine or practices become policy, and “information [is] given with no effort to understand parental values (the ritual of informed consent).”

Is choice possible while in active labor?

De Vries also raises a really critical question with no clear answers—is choice really possible during active labor? He also asks, “should a healthy pregnant woman be allowed to choose a surgical birth? But is it safe? The problem with data…Interestingly, those who think it should be allowed find it safe, and those who oppose it, find it to be unsafe.” When considering where this “choice” of surgical birth comes from, he identifies the following factors:

The desires of women

• Preserve sexual function

• Preserve ideal body

• The need to fit birth into employment

• Options offered by health care system

The desires of physicians

• Manage an unpredictable process

• The limits of obstetric education

Why should we care, anyway?

Another popular phrase is, “it’s not my birth.” I agree with the opinion of Desirre Andrews on this one:

“I do not believe in the saying ‘Not my birth.’ Women are connected together through the fabric of daily life including birth. What occurs in birth influences local culture, reshapes beliefs, weaves into how we see ourselves as wives, mothers, sisters, & women in our community. Your birth is my birth. My birth is your birth. This is why no matter my age or the age of my children it matters to me.”

Victims of circumstance?

While it may sound as if I am saying women are powerlessly buffeted about by circumstance and environment, I’m not. Theoretically, we always have the power to choose for ourselves, but by ignoring, denying, or minimizing the multiplicity of contexts in which women make “informed choices” about their births and their lives, we oversimplify the issue and turn it into a hollow catchphrase rather than a meaningful concept.

Women’s lives and their choices are deeply embedded in a complex, multifaceted, practically infinite web of social, political, cultural, socioeconomic, religious, historical, and environmental relationships.

And, I maintain that a choice is not a choice if it is made in a context of fear.

But, what do we know?

I read an interesting article by anthropologist and birth activist, Robbie Davis-Floyd, in the summer issue of Pathways Magazine. It was an excerpt from a longer article that appeared in Anthropology News, titled “Anthropology and Birth Activism: What Do We Know?” In the conclusion, Davis-Floyd states the following:

“Doctors ‘know’ they are giving women ‘the best care,’ and ‘what they really want.’ Birth activists…know that this ‘best care’ is too often a travesty of what birth can be. And yet on that existential brink, I tremble at the birth activist’s coding of women as ‘not knowing.’ So, here’s to women educating themselves on healthy, safe birth practices–to women knowing what is best for themselves and their babies, and to women rising above everything else.”

I believe that every woman who has given birth knows something about birth that other people don’t know. I also believe that women know what is right for their bodies and that mothers know what is right for their babies. I’m also pretty certain that these “knowings” are often crowded out or obliterated or rendered useless by the large sociocultural context in which women live their lives, birth their babies, and mother their young. So, how do we celebrate and honor the knowings and help women tease out and identify what they know compared to what they may believe or accept to be true while still respecting their autonomy and not denigrating them by characterizing them as “not knowing” or as needing to “be educated”? As I’ve written previously, with regard to education as a strategy for change: People often suggest “education” as a change strategy with the assumption that education is all that is needed. But, truly, do we want people to know more or do we want them to act differently? There is a LOT of information available to women about birth choices and healthy birth options. What we really want is not actually more education, we want them to act, or to choose, differently. Education in and of itself is not sufficient, it must be complemented by other methods that motivate people to act. As the textbook I use in class states, “a simple lack of information is rarely the major stumbling block.” You have to show them why it matters and the steps they can take to get there…

And, as the wise Pam England points out: “A knowledgeable childbirth teacher can inform mothers about birth, physiology, hospital policies and technology. But that kind of information doesn’t touch what a mother actually experiences IN labor, or what she needs to know as a mother (not a patient) in this rite of passage.”

The systemic context…

We MUST look at the larger system when we ask our questions and when we consider women’s choices. The fact that we even have to teach birth classes and to help women learn how to navigate the hospital system and to assert their rights to evidence-based care, indicates serious issues that go way beyond the individual. When we talk about women making informed choices or make statements like, “well, it’s her birth” or “it’s not my birth, it’s not my birth,” or wonder why she went to “that doctor” or “that hospital,” we are becoming blind to the sociocultural context in which those birth “choices” are embedded. When we teach women to ask their doctors about maintaining freedom of movement in labor or when we tell them to stay home as long as possible, we are, in a very real sense, endorsing, or at least acquiescing to these conditions in the first place. This isn’t changing the world for women, it is only softening the impact of a broken and oftentimes abusive system.

And, then I read an amazing story like this grandmother’s story of supporting her non-breastfeeding daughter-in-law and I don’t know WHAT to do in the end. Can we just trust that women will find their own right ways, define their own experiences, and access their own knowings in the context of all the impediments to free choice that I’ve already explored? What if she says, “why didn’t you TELL me?” But, if we share our information we risk polarization. If we keep silent and just offer neutral “support,” regardless of the choice made, then doesn’t it eventually become that the only voice available for her as she strives to make her own best choices is the voice of What to Expect and of hospital policy?

“Our lives are lived in story. When the stories offered us are limited, our lives are limited as well. Few have the courage, drive and imagination to invent life-narratives drastically different from those they’ve been told are possible. And unfortunately, some self-invented narratives are really just reversals of the limiting stereotype…” –Patricia Monaghan (New Book of Goddesses and Heroines, p. xii)

—-

Related posts:

What to Expect When You Go to the Hospital for a Natural Childbirth

Birth & Culture & Pregnant Feelings

Asking the right questions…

Active Birth in the Hospital

Why do I care?

References:

De Vries, Raymond. May 20, 2010. Birthing Ethics: What You Should Know About the Ethics of Childbirth, Webinar presented by Lamaze International.

De Vries, Raymond. Feb. 26-27. U.S. Maternity Care: Understanding the Exception That Proves the Rule. Coalition for Improving Maternity Services (CIMS). 2010 Mother-Friendly Childbirth Forum