Earlier this year I mentioned that I’d used BlogBlooker to convert my blog into a book so that I could copy the text into a year-end Wordle. Anyway, I decided I might as well make the finished blogbook available for download here as an ebook of sorts. It is pretty rough, since it includes comment text as well as “footnotes” of any websites I linked to. And, the formatting of pictures and other elements is a little funky, plus it includes any reviews or giveaways or quotes posts that I did during 2011. But, for anyone who wants it, here is a year of Talk Birth in pdf ebook format. I sent it to myself to read on my iPad and it was really pretty fun! It is a long document—410 page pdf. Enjoy!

Archives

Health Clubs, Heart Health, & Birth

One of the things I enjoy about the book Mother’s Intention: How Belief Shapes Birth, by Kim Wildner is how straightforward, matter-of-fact and unapologetic the author is when exploring concepts, realities, facts, and beliefs about birth. In a section addressing perceived risk and birth, she shares an effective analogy about health clubs and heart disease paralleling the accident-waiting-to-happen mentality of modern obstetrics:

A multitude of things CAN go wrong with any system in the body, but seldom DO. Take the heart/circulatory system for example. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the US. 873 per 100,000 die of heart disease (CDC). (Remember, natural birth is between 6 and 14 per 100,000 in the US, depending on the population.) Some have arteries on the verge of clogging. Some have heart defects they are unaware of. Some have damage they don’t know about. Something could go wrong at any minute and immediately available surgery can undoubtedly save lives.

Using the logic of obstetrics, all health clubs should be in hospitals and all fitness trainers should be cardiac surgeons. Any independent health club with ‘lay’ trainers would be ‘practicing medicine without a license,’ subject to prosecution. It’s for your own good.

In fact, in order to know if a problem is developing, close monitoring and ‘management’ is required. We will need to place straps on the muscles to measure the intensity of the workout. of course, it will be restrictive, but we need to know how hard the muscles are working to know if the heart can take it. We’ll need to monitor heart rate, blood pressure, fluid output. We’ll need to give an IV because with sweat excreted, you could dehydrate, and of course, we simply can’t take the risk of letting you drink anything lest you need emergency surgery….

Later in the book, the author employs another helpful analogy, again using cardiology as an example to make a point about inappropriately applied maternity care interventions:

What if…

You went to the doctor complaining of chest pain…not bad pain, but bothersome. To rule out a heart problem, the caregiver listens to your heart. He scowls, then excuses himself to make a phone call. He comes back in and tells you that you need to be admitted to the hospital for a test that requires the use of a drug. The drug has a low risk of serious complications, which is why you must be in the hospital, but he feels confident in taking that risk.

You go, and within minutes of having the drug administered, you have a heart attack. You are rushed into emergency open-heart surgery. Complications arise, but they are dealt with. You nearly bleed to death, but with a blood replacement you recover.

The repair doesn’t go well, which may mean you will need further surgery later…maybe even a heart transplant. You definitely will need to change your previously active lifestyle.

Later, you discover the call your care provider places wasn’t to a specialist, but an HMO lawyer who advised him not to let you walk out the door, just in case the routine examination missed a serious problem. You also learn there were less dangerous ways to determine if there could be a minor problem.

It turns out, you really did have a minor case of heartburn. All you have been through was avoidable, but “As long as everyone’s ok now…that’s all that matters”…right?

A comment like that, to a mother who has suffered unnecessarily, when she would have–or could have had–the result of a live, healthy baby without such sacrifice, disregards her feelings of loss.

Parents should be expecting more!

In Open Season, by Nancy Wainer, she refers to OBGYN care is referred to as “gynogadgetry.”

In The Doula Guide to Birth, I marked another quote that feels very relevant to the others above: [a March 2006 study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology] “reviewed all fifty-five of ACOG’s current practice bulletins, calling these articles ‘perhaps the most influential publications for clinicians involved with obstetric and gynecological care.’ The study concluded that ‘among the 438 recommendations made by ACOG, less than one third [23 percent] are based on good and consistent scientific evidence.'”

Enough said.

Year End Wordle

I’m working on a 2011 year-end summary post and it is taking me longer to do than I anticipated. So, for now, a delightful year-end Wordle image instead. I just love these! So much fun to see what you’ve been talking about for a year. It was important to me that the Wordle represent my whole year’s worth of blog posts, rather than just the most recent page which is how it automatically works. So, I used the wonders of BlogBooker to turn the last year’s worth of posts into a book and then copied and pasted that text into Wordle for a full-year’s image. (Side note: Guess how many pages the blogbook was…409. Whoa. No wonder I’m having trouble choosing what to put into a year in review post ;-D)

The Illusion of Choice

A choice is not a choice if it is made in the context of fear.

Informed choice is a popular phrase with birth professionals and healthy birth activists. I’ve read impassioned blog posts from doulas and birth activists claiming that if we support women’s right to homebirth, we must also support her “choice” to have an elective cesarean. But, I believe we have constructed a collaborative mythos within the birth activist community that an informed choice is possible for most women. The statistics tell us a different story. I do not believe that women with full ability to exercise their choices would choose many of the things that are typically on the “menu” for birth in mainstream culture.

What’s on the menu?

Women give their blanket “informed consent” to all manner of hospital procedures without the corollary of informed refusal–is a choice a choice when you don’t have the option of saying no?

In many hospitals, women are STILL not allowed to eat during labor despite ample evidence that this practice is harmful–is a choice a real choice if made in the context of hospital “policies” that are not evidence-based?

Women are told that their babies are “too big” and then “choose” a cesarean. Is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of coercion and deception?

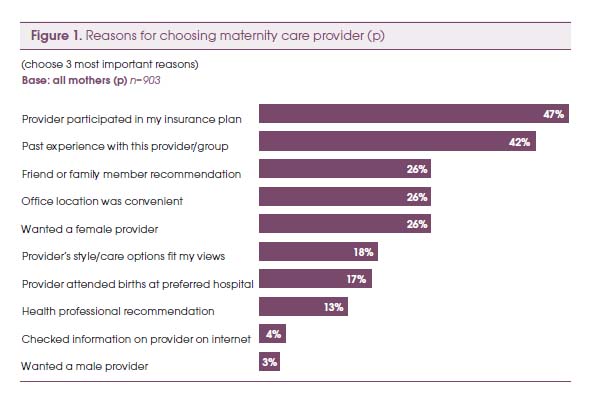

Women choose hospitals and obstetricians that are covered by their insurance companies. Is a choice a real choice when it is made by your HMO?

Women choose hospital birth because they cannot find a local midwife. Is a choice a real choice when it is made in the context of restrictive laws and hostile political climates?

Women often state they are seeking “balanced” birth classes that aren’t “biased” towards natural birth (or towards hospital birth), but is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of misrepresented information? Because, as Kim Wildner notes, balance means “to make two parts equal”–what if the two parts aren’t equal? What is the value of information that appears balanced, but is not factually accurate? Pointing out inequalities and giving evidence-based information does not make an educator “biased” or judgmental–it makes her honest! (though honesty can be “heard” as judgment when it does not reflect one’s own opinions or experiences).

On a somewhat related note, recently, the subject of “quiverfull” families came up amongst my friends and comments were made about feminists needing to support those women’s “choice” to have so many children. However, I worry about women who are making reproductive “choices” in the context of what can be a very repressive religious tradition. Women’s choices about their lives are not always made with free agency. And, that is where some feminist critiques of other women’s choices come from–a critique of the larger context (patriarchy) rather than the woman herself. Is a choice a choice when it is made in the context of oppression?

Where do women get information to make their choices?

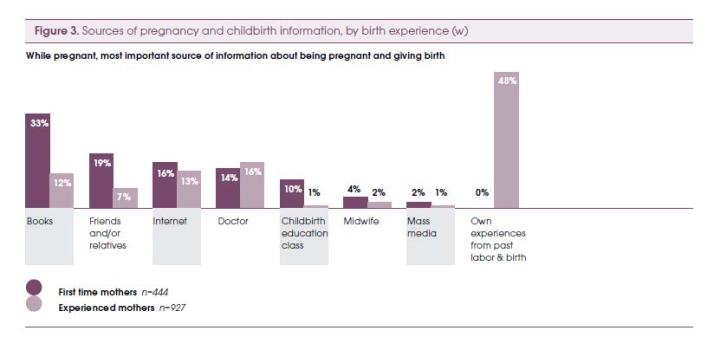

In his 2010 presentation, Birthing Ethics: What You Should Know About the Ethics of Childbirth, Raymond DeVries uses data from the Listening to Mother’s studies to help us understand where women are getting their information about birth—this is the context in which their “informed choices” are being made and this is the context we need to consider.

Our choices in birth and life are profoundly influenced by the systems in which we participate…

Some choices shaped by the system

Women learn from books and experiences of others (and self):

The number one book women learn from is What to Expect When You’re Expecting, which has been number four on NY Times Bestsellers list for over 500 weeks and counting.

According to De Vries, via the Listening to Mothers data, this is what women tell us about how they learn, what they learn, and upon what their choices are based:

Television explains birth

Pain is not your friend

But technology is

Mothers are listening to doctors (and nurses)

Medicalized birth allows mothers to feel capable and confident

Interfering with birth is mostly okay

Our health system works (mostly)

We like choice

We want to be “informed”

He also explains polarization: “We seek information to confirm our opinion. Contrary information does not convince, it polarizes.” How do we share information so that women can make truly informed choices without polarizing?

As advocates, I think we sometimes fall back on the phrase “informed choice” as an excuse not to be outraged, not to despair, and not to give up, because it promises that change is possible if only women change and most of us have access to change at that level.

Birthing room ethics

In another presentation, U.S. Maternity Care: Understanding the Exception That Proves the Rule, DeVries explores the ethical issues surrounding choices in birth, noting that “choice is central at all levels – but can choice do all the moral work?” We wish to respect parental choice, but information does not equal knowledge and we often err on the side of treating them as one and the same. In maternity care, often there is no choice. Tests become routine or practices become policy, and “information [is] given with no effort to understand parental values (the ritual of informed consent).”

Is choice possible while in active labor?

De Vries also raises a really critical question with no clear answers—is choice really possible during active labor? He also asks, “should a healthy pregnant woman be allowed to choose a surgical birth? But is it safe? The problem with data…Interestingly, those who think it should be allowed find it safe, and those who oppose it, find it to be unsafe.” When considering where this “choice” of surgical birth comes from, he identifies the following factors:

The desires of women

• Preserve sexual function

• Preserve ideal body

• The need to fit birth into employment

• Options offered by health care systemThe desires of physicians

• Manage an unpredictable process

• The limits of obstetric education

Why should we care, anyway?

Another popular phrase is, “it’s not my birth.” I agree with the opinion of Desirre Andrews on this one:

“I do not believe in the saying ‘Not my birth.’ Women are connected together through the fabric of daily life including birth. What occurs in birth influences local culture, reshapes beliefs, weaves into how we see ourselves as wives, mothers, sisters, & women in our community. Your birth is my birth. My birth is your birth. This is why no matter my age or the age of my children it matters to me.”

Victims of circumstance?

While it may sound as if I am saying women are powerlessly buffeted about by circumstance and environment, I’m not. Theoretically, we always have the power to choose for ourselves, but by ignoring, denying, or minimizing the multiplicity of contexts in which women make “informed choices” about their births and their lives, we oversimplify the issue and turn it into a hollow catchphrase rather than a meaningful concept.

Women’s lives and their choices are deeply embedded in a complex, multifaceted, practically infinite web of social, political, cultural, socioeconomic, religious, historical, and environmental relationships.

And, I maintain that a choice is not a choice if it is made in a context of fear.

But, what do we know?

I read an interesting article by anthropologist and birth activist, Robbie Davis-Floyd, in the summer issue of Pathways Magazine. It was an excerpt from a longer article that appeared in Anthropology News, titled “Anthropology and Birth Activism: What Do We Know?” In the conclusion, Davis-Floyd states the following:

“Doctors ‘know’ they are giving women ‘the best care,’ and ‘what they really want.’ Birth activists…know that this ‘best care’ is too often a travesty of what birth can be. And yet on that existential brink, I tremble at the birth activist’s coding of women as ‘not knowing.’ So, here’s to women educating themselves on healthy, safe birth practices–to women knowing what is best for themselves and their babies, and to women rising above everything else.”

I believe that every woman who has given birth knows something about birth that other people don’t know. I also believe that women know what is right for their bodies and that mothers know what is right for their babies. I’m also pretty certain that these “knowings” are often crowded out or obliterated or rendered useless by the large sociocultural context in which women live their lives, birth their babies, and mother their young. So, how do we celebrate and honor the knowings and help women tease out and identify what they know compared to what they may believe or accept to be true while still respecting their autonomy and not denigrating them by characterizing them as “not knowing” or as needing to “be educated”? As I’ve written previously, with regard to education as a strategy for change: People often suggest “education” as a change strategy with the assumption that education is all that is needed. But, truly, do we want people to know more or do we want them to act differently? There is a LOT of information available to women about birth choices and healthy birth options. What we really want is not actually more education, we want them to act, or to choose, differently. Education in and of itself is not sufficient, it must be complemented by other methods that motivate people to act. As the textbook I use in class states, “a simple lack of information is rarely the major stumbling block.” You have to show them why it matters and the steps they can take to get there…

And, as the wise Pam England points out: “A knowledgeable childbirth teacher can inform mothers about birth, physiology, hospital policies and technology. But that kind of information doesn’t touch what a mother actually experiences IN labor, or what she needs to know as a mother (not a patient) in this rite of passage.”

The systemic context…

We MUST look at the larger system when we ask our questions and when we consider women’s choices. The fact that we even have to teach birth classes and to help women learn how to navigate the hospital system and to assert their rights to evidence-based care, indicates serious issues that go way beyond the individual. When we talk about women making informed choices or make statements like, “well, it’s her birth” or “it’s not my birth, it’s not my birth,” or wonder why she went to “that doctor” or “that hospital,” we are becoming blind to the sociocultural context in which those birth “choices” are embedded. When we teach women to ask their doctors about maintaining freedom of movement in labor or when we tell them to stay home as long as possible, we are, in a very real sense, endorsing, or at least acquiescing to these conditions in the first place. This isn’t changing the world for women, it is only softening the impact of a broken and oftentimes abusive system.

And, then I read an amazing story like this grandmother’s story of supporting her non-breastfeeding daughter-in-law and I don’t know WHAT to do in the end. Can we just trust that women will find their own right ways, define their own experiences, and access their own knowings in the context of all the impediments to free choice that I’ve already explored? What if she says, “why didn’t you TELL me?” But, if we share our information we risk polarization. If we keep silent and just offer neutral “support,” regardless of the choice made, then doesn’t it eventually become that the only voice available for her as she strives to make her own best choices is the voice of What to Expect and of hospital policy?

“Our lives are lived in story. When the stories offered us are limited, our lives are limited as well. Few have the courage, drive and imagination to invent life-narratives drastically different from those they’ve been told are possible. And unfortunately, some self-invented narratives are really just reversals of the limiting stereotype…” –Patricia Monaghan (New Book of Goddesses and Heroines, p. xii)

—-

Related posts:

What to Expect When You Go to the Hospital for a Natural Childbirth

Birth & Culture & Pregnant Feelings

Asking the right questions…

Active Birth in the Hospital

Why do I care?

References:

De Vries, Raymond. May 20, 2010. Birthing Ethics: What You Should Know About the Ethics of Childbirth, Webinar presented by Lamaze International.

De Vries, Raymond. Feb. 26-27. U.S. Maternity Care: Understanding the Exception That Proves the Rule. Coalition for Improving Maternity Services (CIMS). 2010 Mother-Friendly Childbirth Forum

Birth and the Women’s Health Agenda

In the Fall issue of The Journal of Perinatal Education (Lamaze), there was a guest editorial by perinatologist Michael Klein called “Many Women and Providers are Unprepared for an Evidence-Based Conversation About Birth.” In it he notes:

Childbirth is not on the women’s health agenda in most Western countries…It never has been. Osteoporosis is. Breast health is; violence against women is. Why not childbirth? Because women, understandably, do not want to be judged only by their reproductive capacities. Women are multipotential people. Among many potentialities, they can rise to the top of the academic and corporate world. Giving birth is just one of many things women can do. But now is the time to add childbirth to the women’s health agenda; it is because of the lack of informed decision making that birth should be added to that agenda, lack of information, misinformation, and even disinformation. The time is now.

…What really matters is attitudes and beliefs, which are much more difficult to change than putting away the scissors and hanging some plants. These are systemic issues. (emphasis mine) It is all about anxiety and fear. The doctors are afraid…The women are afraid…Society is afraid and averse to risk.

So how can you make a revolution when so few individuals are unhappy with current maternity care practices? The most unhappy and well-informed women select midwives, if available. The most fearful women select obstetricians. Providers are not going to initiate the revolution to make childbirth a normal rather than high-risk, industrialized activity…Women are going to have to take the lead…

The problem is not that obstetricians are surgeons. They are. The problem is that society has invested surgeons with control over normal childbirth.

I keep wanting to write an article called, “is evidence-based care enough?” because we see this phrase used so often in birth advocacy work. It is kind of the companion phrase to the, “women just need to educate themselves” line of thought, that, quite frankly, is also just not enough. And, I think the reason it isn’t enough—all of our education, all of our books, and all of our evidence—is because it isn’t information itself that really needs to change, it is women’s feelings and beliefs about birth (and the medical system’s feelings and beliefs about it too, in addition to their practices) and changing those sometimes feel like an insurmountable task. As I’ve written before, much of the time it isn’t that we actually want women to know more, we want them to act differently. And, a choice made in a context of fear is not an informed choice at all.

The Value of Sharing Story

“..no matter what her experience in birth was, every mother knows something other people don’t know.”—Pam England

“Stories are medicine…They have such power; they do not require that we do, be, act anything—we need only listen. The remedies for repair or reclamation of any lost psychic drive are contained in stories.” –Clarissa Pinkola Estes

Every woman who has given birth knows something about birth that other people don’t know. She has something unique and powerful to offer.

As birth professionals, we are often cautioned against sharing our personal stories. We must remember that it is her birth and her story, not ours. In doula and childbirth educator trainings, trainees are taught to keep their own stories to themselves and to present evidence-based information so that women can make their own informed choices. As a breastfeeding counselor too, I must remind myself to keep my own personal experiences out of the helping relationship. My formal education is in clinical social work and in that field as well we are indoctrinated to guard against inappropriate self-disclosure in a client-helper setting. In each environment, we are taught how to be good listeners without clouding the exchange with our own “baggage.” The messages are powerful—keep your own stories out of it. Recently, I have been wondering how this caution might impact our real-life connections with women?

Nine months after I experienced a powerful miscarriage at home at 15 weeks, a good friend found out at 13 weeks that her baby died. As I had, she decided to let nature take its course and to let her body let go of the pregnancy on its own timetable, rather than a medical timetable. When she emailed me for support, it was extremely difficult to separate our experiences. I kept sharing bits and pieces of my own loss experiences and then apologizing and feeling guilty for having violated the “no stories” rule. I kept telling her, “I know this isn’t about me, but I felt this way…” I told her about choosing to take pictures of the baby and to have a ceremony for him at home. That I wished I had gotten his footprints and handprints. The kinds of personal sharing that may have been frowned upon in my varied collection of professional trainings. After several apologies of this sort, I began to reflect and remembered that what I hungered for most in the aftermath of my own miscarriage was other women’s voices and stories. Real stories. The nitty gritty, how-much-blood-is-normal and did-you-feel-like-you-were-going-to-die, type of stories. Just as many women enjoy and benefit from reading other women’s birth stories, I craved real, deep, miscarriage-birth stories. These stories told me the most about what I needed to know and more than organization websites or “coping with loss” books ever could.

I had a similar realization the following month when considering the effectiveness of childbirth classes and trying to pin down what truly had reached me as a first time mother. The question I was trying to answer as I considered my own childbirth education practice was how do women really learn about birth? What did I, personally, retain and carry with me into my own birth journey? The answer, for me, was again, story.

On this blog, I have a narrative about my experiences during my first pregnancy with being able to feel my baby practicing breathing while in-utero. More than any other post on the site, this post receives more comments on an ongoing basis from women saying, “thank you for sharing”–that the story has validated their own current experience. In this example, rather than getting what they need from books, experts, or classes, women have found what they needed from story and, indeed, most of them reference that it was the only place they were able to find the information they were seeking.

And finally, as breastfeeding counselor, during monthly support meetings, I cannot count the number of times I’ve seen mothers’ faces fill with relief when another mother validates her story with a similar one.

So, what is special about story as a medium and what can it offer to women that traditional forms of education cannot? Stories are validating. They can communicate that you are not alone, not crazy, and not weird. Stories are instructive without being directive or prescriptive. It is very easy to take what works from stories and leave the rest because stories communicate personal experiences and lessons learned, rather than expert direction, recommendations, or advice. Stories can also provide a point of identification and clarification as a way of sharing information that is open to possibility, rather than advice-giving.

Cautions in sharing stories while also listening to another’s experience include:

- Are you so busy in your own story that you can’t see the person in front of you?

- Does the story contain bad, inaccurate, or misleading information?

- Is the story so long and involved that it is distracting from the other person’s point?

- Does the story communicate that you are the only right person and that everyone else should do things exactly like you?

- Is the story really advice or a “to do” disguised as a story?

- Does the story redirect attention to you and away from the person in need of help/listening?

- Does the story keep the focus in the past and not in the here and now present moment?

- Is there a subtext of, “you should…”?

Several of these self-awareness questions are much bigger concerns during a person-to-person direct dialogue rather than in written form such as blog. In reading stories, the reader has the power to engage or disengage with the story, while in person there is a possibility of becoming stuck in an unwelcome story. Some things to keep in mind while sharing stories in person are:

- Sensitivity to whether your story is welcome, helpful, or contributing to the other person’s process.

- Being mindful of personal motives—are you telling a story to bolster your own self-image, as a means of pointing out others’ flaws and failings, or to secretly give advice?

- Asking yourself whether the story is one that will move us forward (returning to the here and now question above).

While my training and professional background might suggest otherwise, my personal lived experience is that stories have had more power in my own childbearing life than most other single influences. The sharing of story in an appropriate way is, indeed, intimately intertwined with good listening and warm connection. As the authors of the book, Sacred Circles, remind us “…in listening you become an opening for that other person…Indeed, nothing comes close to an evening spent spellbound by the stories of women’s inner lives.”

Molly Remer, MSW, ICCE, CCCE is a certified birth educator, writer, and activist who lives in central Missouri with her husband and children. She is an LLL Leader, a professor of Human Services, and the editor of the Friends of Missouri Midwives newsletter. She blogs about birth, women, and motherhood at https://talkbirth.wordpress.com.

This is a preprint of The Value of Sharing Story, an article by Molly Remer, MSW, ICCE, published in Midwifery Today, Issue 99, Autumn 2011. Copyright © 2011 Midwifery Today. Midwifery Today’s website is located at: http://www.midwiferytoday.com/

Affordable Fetal Model

Two things to know about me:

1. I love dolls.

2. I love bargains.

For quite a while, I’ve wanted a realistic baby model to use in my birth classes. My ideal model could be used both for demonstrations of fetal positioning in the pelvis and also for demo’ing newborn care and possibly breastfeeding. Most fetal models sold by CBE supply companies range from $60-150. I usually use a Bitty Baby doll to demo newborn care and breastfeeding (a third thing to know about me is that my love of bargains makes an exception when it comes to American Girl dolls. I have an embarrassing number of AG dolls and vast quantities of accessories. I’ve had this Bitty Baby for over 10 years, I didn’t buy her to use in class). In my knitted uterus, resides a cute little baby doll I bought at Target for $5. Neither of these dolls works at all for fetal positioning or with my demonstration pelvis.

So, imagine my delight when I found a nearly perfect model newborn at Kmart yesterday while my son was picking out his birthday presents. I named her Sasha AND, get this, she was $20. In a bonus twist, unlike 99.9% of the dolls in the store, she did not come with a bottle! (There is a bottle pictured with a different doll on the back of the box.) She did come with a little cloth diaper, a onesie, a band to cover her cord stump (yes, she seems to have one, but it could just be a dramatic “outie”!), a little outfit, a hat, and socks. Called La Newborn (nursery doll), she is made by Berenguer.

The only drawback is she is not very flexible and so would be hard to use comfortably for things like practicing putting on diapers. Her fairly flexed permanent body position does make her absolutely ideal for use for fetal positioning and even for swaddling or babywearing practice. I originally planned to take her arms and legs off to fill with plastic pellets to add weight, but I’d don’t think I’m going to bother. While nothing near the weight of a real baby, she is made from good quality vinyl.

After looking these dolls up various places online, I’m now thinking I should have bought the remaining one or two that they had at K-Mart. They don’t seem to be widely available for the $20 price.

This morning, my older son helped me take all kinds of pictures of my new toy—I mean, teaching aid!—today (yet another of the many benefits of having an 8 year old in the house!). So, this is a photo-heavy post!

If the demo pelvis had a coccyx joint, the baby would fit perfect through. As it is, her head does get stuck on it (good teaching moment about the importance of active positions for birthing!)

For sizing purposes—while I think she appears to be the perfect, realistic size when held up to my belly as a fetal model for positioning, when held in arms, she is more the size of a preemie baby (maybe a 31 weeker or so). She is about 15 inches.

Lann wanted me to take this one—“make them guess who’s the real baby!!!”—conveniently, Alaina closed her eyes for this picture, making identification of the real baby even trickier…

—

Edited to add, Baby Sasha later experienced an unfortunate accident and had to be replaced. See Fetal Model Update post for pictures.

Active Birth in the Hospital

The vast majority of my birth class clients are women desiring a natural birth in a hospital setting. My classes are based on active birth and include a lot of resources for using your body during labor and working with gravity to help birth your baby. Sometimes I feel like active birth and hospital birth are incompatible—i.e. the woman’s need for activity runs smack dab into the hospital’s need for passivity (i.e. “lie still and be monitored”). So, I was delighted to discover this awesome series of photos from ICAN of Atlanta of VBAC mothers laboring on the monitors. It IS possible to remain active and upright, even while experiencing continuous fetal monitoring.

In my own classes, we talk about how to use a hospital bed without lying down—the idea that a hospital bed can become a tool you can use while actively birthing your baby. Here is a pdf handout on the subject:How to Use a Hospital Bed without Lying Down. In this handout, I offer these tips for using the bed as an active assistant, rather than a place to be “tied down”:

While being monitored and/or receiving IV fluids that limit mobility, try:

- Sitting on a birth ball and leaning on bed

- Sitting on bed

- Sitting on bed and lean over ball (also on bed)

- Kneeling on bed

- Hands and knees on bed

- Standing up and leaning on bed

- Leaning back of bed up and resting against it on your knees

- Bringing a beanbag chair, putting it on the bed and draping over it (can also make “nest” with pillows)

- Partner sitting on bed and woman leaning on him/supported squats with him

- Partner sitting behind woman on bed (with back leaned up as far as it will go)

While giving birth, try:

- Hands and knees on bed

- Kneeling with one leg up (on bed like a platform or “stage”)

- Holding onto raised back of bed and squatting or kneeling

- Squatting using squat bar

While most of the above tips can be used during monitoring, additional ideas for coping with a simultaneous need for monitoring AND activity include:

- Kneel on bed and rotate hips

- Sit on edge of bed and rock or rotate hips

- Sit on ball or chair right next to bed (partner can hold monitor in place if need be)

If something truly requires being motionless, it can be helpful to have some breath awareness techniques available in your “bag of tricks.” One of my favorites is: Centering for Birth

Some time ago, a blog reader posed the question, can I really expect to have a great birth in a hospital setting? I definitely think it is possible! I also think there is a lot you can do in preparation for that great hospital birth! When planning a natural birth in the hospital, it is important to consider becoming an informed birth consumer. I always tell my clients that an excellent foundation for a simple, effective, evidence-based birth plan is to base it on Lamaze’s Six Healthy Birth Practices. My own pdf handout summarizing the practices is also available: Six Healthy Birth Practices. Don’t forget there is also a great video series of the birth practices in action! You might also want to get a copy of the book Homebirth in the Hospital. And, check out this post from Giving Birth with Confidence: Six Tips for Gentle but Effective Hospital Negotiations.

Before you go in to the hospital to birth your baby, make sure you have some ideas about this very popular question, how do I know if I’m really in labor?

And, finally, be prepared for the hospital routines you may encounter by reading my post: What to Expect When You Go to the Hospital for a Natural Childbirth.

For some other general ideas about active birth, read my post about Moving During Labor (written for a blog carnival in 2009).

Best wishes for a beautiful, healthy, active hospital birth! You can do it!

Book Review: Doulas’ Guide to Birthing Your Way

Book Review: Doulas’ Guide to Birthing Your Way

Authors: Jan Mallak & Teresa Bailey, 2010.

ISBN: 978-0-9823379-7-4

$15.37 – $21.95, 188 pages, softcover

Hale Publishing: http://www.ibreastfeeding.com/

Reviewed by Molly Remer

Geared towards pregnant women, Doulas’ Guide to Birthing Your Way is written in a simplistic manner using short, direct sentences. While in some ways this approach makes the information readily accessible, it can also feel unsophisticated in places. However, while the writing style is basic, the content is not. The Doulas’ Guide is a book that really “goes beyond” the information traditionally offered in birth preparation books, covering topics many parents typically may not have considered prenatally such as natural birth vs. birthing naturally, physical comfort preference styles, visualization, being a savvy consumer, blessingways, and taking pictures of the placenta. The information is refreshingly practical and hands-on. Chapters cover the critical importance of the human environment, “five arms of doula support,” birth preparation, one chapter for each stage of labor including separate chapter for immediate postpartum, a section about cesarean birth and VBAC, and a breastfeeding chapter. There is an excellent section on postpartum care including a PPD symptoms chart. I was a little taken aback by a blithe comment, “Just think of it as an alternate birth route!” regarding cesareans.

Doulas’ Guide contains good, helpful snapshots throughout the text. Dads will like the plethora of labor support skills and ideas and the accompanying photographs. The book advocates preparation of a “birth vision” and includes examples at the end of the book (including cesarean birth options).

The variety of checklists, key questions, tables with reference information, bullet points, and pictures keep the pace of Doulas’ Guide to Birthing Your Way snappy and digestible. This book covers lots of ground and packs a lot of information into under 200 pages!

—–

Disclosure: I received a complimentary copy of this book for review purposes.

Women and Knowing

I read an interesting article by anthropologist and birth activist, Robbie Davis-Floyd, in the summer issue of Pathways Magazine. It was an excerpt from a longer article that appeared in Anthropology News, titled “Anthropology and Birth Activism: What Do We Know?” In the conclusion, Davis-Floyd states the following:

“Doctors ‘know’ they are giving women ‘the best care,’ and ‘what they really want.’ Birth activists…know that this ‘best care’ is too often a travesty of what birth can be. And yet on that existential brink, I tremble at the birth activist’s coding of women as ‘not knowing.’ So, here’s to women educating themselves on healthy, safe birth practices–to women knowing what is best for themselves and their babies, and to women rising above everything else.” –Robbie Davis-Floyd

I believe that every woman who has given birth knows something about birth that other people don’t know. I also believe that women know what is right for their bodies and that mothers know what is right for their babies. I’m also pretty certain that these “knowings” are often crowded out or obliterated or rendered useless by the large sociocultural context in which women live their lives, birth their babies, and mother their young. So, how do we celebrate and honor the knowings and help women tease out and identify what they know compared to what they may believe or accept to be true while still respecting their autonomy and not denigrating them by characterizing them as “not knowing” or as needing to “be educated”?

Additionally, with regard to education as a strategy for change, I’m brought back to a point I raise in my community organizing class: People often suggest “education” as a change strategy with the assumption that education is all that is needed. But, truly, do we want people to know more or do we want them to act differently? There is a LOT of education available to women about birth choices and healthy birth options. What we really want is not actually more education, we want them to act, or to choose, differently. Education in and of itself is not sufficient, it must be complemented by other methods that motivate people to act. As the textbook I use in class states, “a simple lack of information is rarely the major stumbling block.” You have to show them why it matters and the steps they can take to get there…